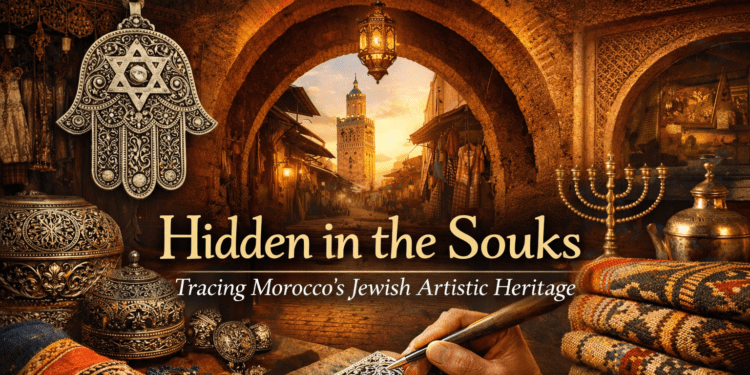

In the narrow alleyways of Morocco’s ancient mellahs, where hammered silver once rang like sacred music and the scent of tanned leather mingled with spice-laden air, Jewish artisans shaped more than beautiful objects — they shaped memory itself.

Today, as visitors wander through the mellahs of Fez, Marrakech, Essaouira, and Meknes, echoes of that world remain. But the hands that once brought silver filigree to life, wove carpets heavy with symbolism, and prepared homes for luminous Jewish holidays have largely fallen silent.

This is the story of those hidden wonders — the artistry, the rituals, and the disappearing holidays that once animated Moroccan Jewish life.

The Golden Hands of the Mellah

For centuries, Jewish artisans stood at the heart of Morocco’s decorative arts. In Fez, the mellah was not only a residential quarter — it was an ecosystem of creativity. Silversmiths bent over delicate filigree work, crafting bridal jewelry, Torah ornaments, and amulets believed to carry both protection and blessing.

Jewish silversmiths were renowned for their precision. They blended Moroccan geometric motifs with Jewish symbols such as the Star of David and Hamsa designs, creating pieces that traveled far beyond Morocco through Saharan and Mediterranean trade routes. Visiting merchants carried their jewelry across North Africa and into Europe, embedding Moroccan Jewish artistry into global markets.

In Meknes and Fez, this era became known as a golden age of craftsmanship. Techniques were passed from father to son in small, tightly knit workshops. Apprentices learned not only how to hammer silver but how to read its spiritual weight — when an ornament was meant for a bride, a Torah scroll, or a newborn child.

But with the mid-20th-century emigration of Moroccan Jews — particularly following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and Morocco’s independence in 1956 — this artisanal chain was abruptly broken. Families left for Israel, France, and Canada. Workshops closed. Skills that had survived for centuries faded within a generation.

Threads of Shared Craft

Jewish artisans were also vital to Morocco’s textile traditions, particularly in Essaouira, once home to a thriving Jewish majority. Here, Jewish and Muslim weavers collaborated to create intricate carpets blending Berber symbolism with Jewish patterning.

Certain motifs — protective diamonds, stylized hands, fertility symbols — appeared across communities, revealing a shared visual language. Jewish merchants played a crucial role in exporting Moroccan carpets to European markets, strengthening economic and cultural ties across the Mediterranean.

Even today, antique Zemmour and Atlas carpets bear witness to that intertwined heritage. Though the Jewish weavers are largely gone, their design vocabulary survives in patterns still woven in rural workshops.

Leather and Life in Marrakech

In Marrakech, Jewish tanners and leather artisans were integral to the city’s famed souks and tanneries. Working alongside Muslim craftsmen, they helped perfect techniques of tanning and dyeing hides that gave Moroccan leather its global reputation.

Beyond belts and bags, leather also served ritual life. Torah cases, tefillin pouches, and ceremonial objects were fashioned with care, merging daily craftsmanship with sacred purpose.

The mellah of Marrakech once pulsed with this energy — artisans at work by day, families preparing for Shabbat by evening. Today, restoration projects preserve the architecture, but the communal rhythm that sustained it has largely vanished.

The Holidays That Lit the Courtyard

Handicrafts were not isolated artistic expressions; they were woven into the cycle of Jewish holidays that defined Moroccan Jewish identity.

On Mimouna — the joyful post-Passover celebration unique to North African Jewry — homes were transformed into radiant displays of hospitality. Silver trays gleamed with mufleta pancakes, honey, butter, and symbols of abundance. Neighbors — Jewish and Muslim alike — crossed thresholds in shared celebration.

During Hiloula pilgrimages honoring revered rabbis, families carried handcrafted candles, textiles, and amulets to gravesites, blending mysticism with communal devotion.

Henna ceremonies before weddings featured elaborate jewelry crafted by Jewish silversmiths, each piece holding generational memory. Passover tables displayed embroidered linens created by Jewish women whose needlework carried as much artistry as the silver on the sideboard.

As emigration emptied the mellahs, these traditions fragmented. In Israel, France, and Montreal, Moroccan Jews recreated Mimouna and preserved beloved recipes — but the Moroccan courtyard, the shared neighborly exchange, the texture of place, could not be fully transplanted.

Today in Morocco, Mimouna is increasingly recognized as part of national heritage, yet in many cities, it survives more as cultural memory than lived communal ritual.

Decline and Rediscovery

The departure of nearly 250,000 Moroccan Jews in the mid-20th century reshaped the country’s artisanal landscape. Entire trades — especially filigree silverwork practiced almost exclusively by Jews — declined sharply.

Yet memory has not disappeared.

In Casablanca, the Jewish Museum of Casablanca — the only Jewish museum in the Arab world — preserves ritual objects, textiles, marriage contracts, and jewelry that tell the story of a once-vibrant community. Exhibitions highlight how Jewish artisans shaped Morocco’s aesthetic vocabulary.

Cultural initiatives and festivals in Fez and Essaouira increasingly celebrate Morocco’s pluralistic past, recognizing Jewish contributions not as marginal footnotes but as foundational threads in the national tapestry.

A new generation of Moroccan artisans — both Jewish descendants abroad and Muslim craftsmen within Morocco — is beginning to revisit old techniques. Some study antique pieces to reconstruct forgotten filigree methods. Others collaborate across continents, blending tradition with contemporary design.

This revival is not nostalgic; it is reclamation.

Beyond Objects: A Shared Moroccan Soul

What makes Moroccan Jewish handicrafts so deeply moving is not merely their beauty but their embodiment of coexistence. Jewish and Muslim artisans worked side by side for centuries, shaping a shared visual culture that transcended religious boundaries.

Silver necklaces, woven carpets, carved wooden Torah arks — these were products of collaboration, conversation, and mutual influence. The mellah was not isolated from the medina; it was interwoven with it.

Today, as travelers explore Morocco’s restored synagogues, wander through ancient markets, or visit heritage museums, they encounter more than artifacts. They encounter the memory of a world where faiths intersected through craftsmanship.

Why This Story Matters Now

In an era when cultural identities are often framed in isolation, Morocco’s Jewish handicraft legacy offers a different narrative — one of shared creation.

The disappearing Jewish holidays of Morocco remind us that traditions are fragile. Without lived communities, rituals fade. Without artisans, symbols lose their tactile meaning.

But the renewed interest in Moroccan Jewish heritage — from restoration projects to museum exhibitions — signals hope. It suggests that memory, when honored, can inspire revival.

For travelers seeking depth beyond postcard Morocco, the true hidden wonders lie not only in palaces and riads, but in the silverwork of a forgotten workshop, the embroidered cloth of a Passover table, the whispered memory of Mimouna in a quiet courtyard.

The legacy of Moroccan Jewish handicrafts is not merely a story of decline.

It is a story of resilience — hammered in silver, woven in wool, dyed in leather, and carried in the hearts of a diaspora that still remembers the rhythm of the mellah.

And remembering keeps it alive.

By Meyer Harroch | New York Jewish Travel Guide

Meyer Harroch is the Founder and Publisher of the New York Jewish Travel Guide, documenting Jewish heritage, life, and culture worldwide while promoting tourism and global destinations.