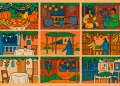

Sukkot might have the same core mitzvot everywhere—build a hut, eat in it, vibe under the stars—but how Jews celebrate it around the world is anything but uniform.

From balconies in Sukkoth draped in blue and white overlooking the Aegean, to lantern-lit courtyards in Baghdad, to Persian carpet–lined huts in Central Asia, communities have always added their own flair, making the holiday feel both familiar and totally local.

Here are some global Sukkot traditions you might not know.

How do Jews celebrate Sukkot around the world?

American and Canadian Jews: In the U.S. and Canada, Sukkot decorations blend Jewish tradition with classic fall aesthetics. Sukkot often arrives just as leaves are turning, so sukkahs fill up with pumpkins, gourds, and corn stalks, echoing the seasonal imagery of Thanksgiving. Branches bursting with red and gold leaves lean against the walls, while paper chains swoop across the ceiling like colorful garlands. While many families eat Thanksgiving food in their Sukkahs, many others traditionally eat pizza and will make a “pizza in the hut” joke.

Bukharan Jews (Central Asia): Bukharan Jews traditionally line their sukkot with richly patterned Persian carpets and embroidered textiles, creating an opulent, living-room-like space. In some families, evenings in the sukkah featured live music or singing.

Yemenite Jews: Yemenite Jews often build their sukkahs on rooftops, using woven date palm branches as schach. Decorations lean heavily on pomegranates, citrus, and natural produce—no paper chains here.

Syrian and Lebanese Jews: Families hang whole etrogim and pomegranates from sukkah ceilings, sometimes alongside garlands of fruit. Holiday meals feature stuffed vegetables and citrus-infused desserts that tie in with the harvest theme.

Greek and Turkish Jews: Balkan Jews build sukkot on balconies, sometimes cantilevered over the street. Interiors are decorated with white linens and blue fabrics, evoking the sky and sea.

Ethiopian Jews: Historically, Beta Israel communities did not build sukkahs. Instead, they gathered outdoors near rivers for communal prayers and agricultural celebrations during a festival that coincides with Sukkot. In Israel today, many blend traditional customs with sukkah-building.

Moroccan Jews: Moroccan sukkot overflow with embroidered fabrics, carpets, and hanging fruit like pomegranates, citrus, and grapes. Guests are welcomed with mint tea and pastries, and special prayers or decorations honor the ushpizin. These traditions remain vibrant in Israel and Moroccan diaspora communities today.

Iraqi Jews: Families built large sukkot in central courtyards, decorated with woven mats, hanging fruit, and colored glass lanterns that made the sukkah glow at night. Extended families often gather in one big sukkah.

Indian Jews: Indian Jewish communities build sukkot with woven palm leaves, bamboo, and local flowers, often on rooftops or in courtyards. Decorations feature bright garlands and fruits like bananas and coconuts, reflecting the tropical harvest. Meals include rice dishes, spiced vegetables, and sweets made with coconut and jaggery, giving the holiday a distinctly Indian flavor. In Cochin, families traditionally welcomed neighbors and friends into their sukkot for shared meals and blessings.

Ashkenazi Europe: In 18th- and 19th-century Eastern Europe, sukkot were decorated with intricate paper cuts of the ushpizin and delicate birds made from hollowed eggshells. Tables were filled with seasonal dishes like apple strudel, stuffed cabbage, and kreplach, while in Germany, meals often ended with lebkuchen—spiced honey cookies with fruit and nuts. Today, Jewish families in Europe follow many of those same traditions, though there usually are no eggshells to be found.

Spanish-Portuguese Jews: Sephardic communities in Amsterdam, London, and across the Caribbean decorate their sukkot with white linens, citrus fruits, and fresh greenery. In cities, sukkot are often built against synagogue walls or in courtyard gardens. In Curaçao and Suriname, families incorporate local tropical plants, blending Iberian tradition with Caribbean abundance.

Latin American Jews: Jewish communities in Brazil and Argentina adapt Sukkot décor to the Southern Hemisphere’s springtime harvest, using mangoes, coconuts, palm leaves, and vibrant flowers. In Argentina and Uruguay, families often gather for asado (barbecue) in the sukkah, merging Jewish ritual with beloved local food culture.

South African Jews: South African Sukkots draw on both Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions, decorated with local greenery and bright produce in the warm early-summer weather. It’s common for families to host braais (barbecues) in the sukkah, bringing a distinctly South African flavor to the festival.

Israeli Jews: In Israel, sukkot reflect the country’s diverse Jewish communities. Porches and balconies transform into sukkot draped with plastic fruit garlands, printed ushpizin posters, and strings of lights sold in local markets. Moroccan fabrics, Ashkenazi paper chains, and Sephardic citrus decorations often appear side by side, creating a vibrant blend of global customs in one place.